We have all heard the “doom and gloom” statistics about rising health care spending, and maybe even some of them have begun to sink in since the roll-out of the Affordable Care Act.

We have all heard the “doom and gloom” statistics about rising health care spending, and maybe even some of them have begun to sink in since the roll-out of the Affordable Care Act.

For many reasons, the federal government is working to curb health care expenditures, but many of the processes currently attributed to “Obamacare” have been in the works for a long time. As an example, the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 introduced the Inpatient Prospective Payment System; this system encouraged participating hospitals to voluntarily report performance data to avoid payment reductions. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 went further by mandating the development of what we now know as pay-for-performance or value-based purchasing (used interchangeably).

In 2012, the Institute of Medicine published “Best Care at Lower Cost: the Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” In this report, recommendation 9 refers to performance transparency: making data related to “quality, prices and cost, and outcomes of care” available to consumers.

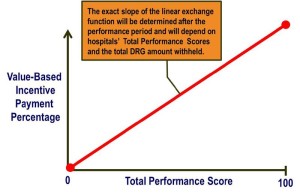

What does this mean? Value-based purchasing in health care is supposed to reward better value, patient outcomes, and innovations – instead of just volume of services (read more). It is funded by participating institutions based on withholding a set percentage (1.25% currently) of their estimated annual Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) payments from Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The percentage is increasing every year and will be 2% by 2017.

What does this mean? Value-based purchasing in health care is supposed to reward better value, patient outcomes, and innovations – instead of just volume of services (read more). It is funded by participating institutions based on withholding a set percentage (1.25% currently) of their estimated annual Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) payments from Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The percentage is increasing every year and will be 2% by 2017.

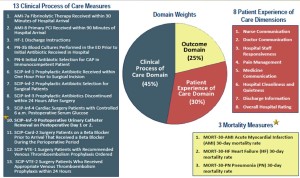

For FY2014, the elements of value-based purchasing have been updated to include the Clinical Process of Care Domain, Patient Experience of Care Domain, and a new Outcomes Domain. The amount that each of these domains contributes to the eventual DRG payment return at the end of the year is 45%, 30%, and 25%, respectively. Scores in each domain are calculated based on an institution’s improvement compared to its own historical performance and a comparison against national benchmarks (read more).

For FY2014, the elements of value-based purchasing have been updated to include the Clinical Process of Care Domain, Patient Experience of Care Domain, and a new Outcomes Domain. The amount that each of these domains contributes to the eventual DRG payment return at the end of the year is 45%, 30%, and 25%, respectively. Scores in each domain are calculated based on an institution’s improvement compared to its own historical performance and a comparison against national benchmarks (read more).

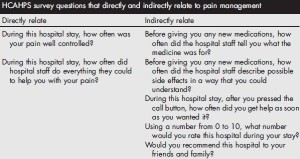

The Patient Experience Domain is assessed using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey. HCAHPS consists of 32 questions, publicly reports its results 4 times a year on http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov, and contains 7 questions that directly or indirectly relate to pain. For details, please see my previous post “Why We Need Acute Pain Medicine Specialists.”

How do we as anesthesiologists address the need for acute pain medicine physicians and have a positive impact on the patient experience? We can take the lead in developing multimodal perioperative pain management protocols (1). For total joint arthroplasty, many of these protocols emphasize opioid-sparing regional anesthesia techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks (PNB) and perineural catheters. These techniques decrease patients’ reliance on opioids for postoperative pain management and are also associated with fewer opioid-related side effects, better sleep, and higher satisfaction (2). In addition, greater selectivity in the PNB technique included in a multimodal protocol may even lead to greater functional achievements for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients which generates additional value (3). For more information about TKA perioperative pain management and improving rehabilitation outcomes, please see my previous post “Regional Anesthesia & Rehabilitation Outcomes after Knee Replacement.”

Anesthesiologists can also add value through cost savings for the hospital. More effective pain management can prevent inadvertent admissions or readmissions due to pain. In addition, an effective multimodal analgesic protocol can directly or indirectly prevent hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). HACs are considered by CMS to be “never events” and supposedly preventable (4); hospitals reporting HACs as secondary diagnoses are not entitled to CMS payments for related care. Examples of HACs include: urinary and vascular catheter-related infections, surgical site infections, DVT/PE, pressure ulcers, and inpatient falls leading to injury.

There remains substantial controversy related to the potential association between regional anesthesia and inpatient falls (5, 6). We do know that falls, when they occur, are associated with worse outcomes for patients and higher resource utilization (7) and that falls may occur in lower extremity joint replacement patients with or without PNB (8). For these reasons, these patients should always be treated as high fall risk, and anesthesiologists can take the lead in developing fall prevention education and fall reduction programs to keep them safe.

There remains substantial controversy related to the potential association between regional anesthesia and inpatient falls (5, 6). We do know that falls, when they occur, are associated with worse outcomes for patients and higher resource utilization (7) and that falls may occur in lower extremity joint replacement patients with or without PNB (8). For these reasons, these patients should always be treated as high fall risk, and anesthesiologists can take the lead in developing fall prevention education and fall reduction programs to keep them safe.

In summary, pay for performance in perioperative pain management is already here. The HCAHPS survey assesses the Patient Experience Domain and can be heavily influenced by the effectiveness of pain management. There are clear opportunities for anesthesiologists to take an active role in adding value and minimizing risks for surgical patients in the perioperative period.

References:

- Hebl JR, Kopp SL, Ali MH, Horlocker TT, Dilger JA, Lennon RL, Williams BA, Hanssen AD, Pagnano MW. A comprehensive anesthesia protocol that emphasizes peripheral nerve blockade for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87 Suppl 2:63-70.

- Ilfeld BM. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks: a review of the published evidence. Anesth Analg 2011;113:904-25.

- Mudumbai SC, Kim TE, Howard SK, Workman JJ, Giori N, Woolson S, Ganaway T, King R, Mariano ER. Continuous Adductor Canal Blocks Are Superior to Continuous Femoral Nerve Blocks in Promoting Early Ambulation After TKA. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2014;472:1377-83.

- Hospital-acquired condition (HAC) in acute inpatient payment system (IPPS) hospitals. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/Downloads/HACFactsheet.pdf

- Ilfeld BM, Duke KB, Donohue MC. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2010;111:1552-4.

- Memtsoudis SG, Danninger T, Rasul R, Poeran J, Gerner P, Stundner O, Mariano ER, Mazumdar M. Inpatient falls after total knee arthroplasty: the role of anesthesia type and peripheral nerve blocks. Anesthesiology 2014;120:551-63.

- Memtsoudis SG, Dy CJ, Ma Y, Chiu YL, Della Valle AG, Mazumdar M. In-hospital patient falls after total joint arthroplasty: incidence, demographics, and risk factors in the United States. The Journal of arthroplasty 2012;27:823-8 e1.

- Johnson RL, Kopp SL, Hebl JR, Erwin PJ, Mantilla CB. Falls and major orthopaedic surgery with peripheral nerve blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:518-28.