When I matched for residency, it was an interesting time for anesthesiology as a specialty because it wasn’t super competitive. I believe that had it to do with a miscalculation in terms of what the demand for anesthesia services would be in the future. But as I finished my residency in 2003, I knew I was going to do a subspecialty fellowship in pediatric anesthesiology, but I was also very interested in a regional anesthesia fellowship. At the time there were very few regional anesthesia fellowship programs, but I was convinced that acute pain and regional anesthesia in kids was a great path forward as a specialty. There was an opportunity to fill a need by providing better non-opioid pain management for children.

I really thought when I finished that I would be a purely clinical anesthesiologist but I got the bug for research. I feel like it was a little bit late in my career. Up to this point, I had successfully avoided research all throughout undergrad, all throughout medical school and almost all of my residency. I didn’t participate in my first research study until the very end of my residency.

Then as a fellow I had a chance to work on a couple of different projects and write case reports. That was a turning point. I discovered this was an interesting way to share information. And I thought, well if I’m going to start my career somewhere, I should start out in academics or at least just give it a shot.

One of my mentors from residency had given me some good advice. He told me you can do anything for five years. You can choose private practice or choose academics. There’s really no wrong answer but you should decide every five years whether you stay or go and it should always be an active decision. You shouldn’t just passively stay anywhere. You want to make sure that you’re on the right track in terms of your career, that you’re still being challenged and you’re still enjoying what you do.

My chair at the time, Dr. Ron Pearl, helped me find my first job at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). They were looking for a pediatric-trained anesthesiologist to help cover pediatric call. UCSD has the Regional Burn Center for the area and provides care for kids and adults. They were looking for a pediatric-trained anesthesiologist who felt comfortable with acute pain and could provide anesthesia services for those patients when they needed dressing changes on the ward or in the operating room for debridement and skin grafts.

In addition, they had high-risk OB and a NICU with some challenging premature neonates who sometimes would need emergency surgery. They also wanted coverage for a hand surgeon with a mixed adult and pediatric practice who worked in the outpatient surgery center. I was told right off the bat that about a quarter of my clinical time would be spent doing pediatrics and then the other seventy-five percent would be taking care of adults.

So I was mainly trying to focus on taking good care of patients. That’s the reason why I was attracted to medicine and felt this is where I am supposed to be. Over the course of my career I’ve just tried to find where the need is and address it. I think in anesthesiology one of the things that maybe self-selects us to the specialty is we are very good at filling gaps and fixing problems. Where I’ve ended up is very much a result of trying to figure out where the gaps are and how to fill them.

BagMask: I think it’s very interesting to talk about filling needs and filling gaps. Sometimes we identify these gaps on our own. Other times we are asked to help fill a need in an area in which we do not have much expertise or maybe never thought about being involved in before. How did you identify those needs and gaps? And why get involved in projects?

Dr. Mariano: I think that’s just one of those challenging questions when you’re trying to pass the answers onto others. I’ve found myself more recently in the role of mentor and coach for various other people that I’ve had a chance to interact with sometimes at the same institution or afar. And I don’t have great answers for it only because I feel like I’m still learning even 15 years outside of residency.

I can say things what worked for me early on in my career were being open-minded and looking at potential opportunities as just that – opportunities – and not as necessarily more work. And I’ll share a couple examples that both revolve around my first job.

I started working in outpatient surgery and at the time that was not an attractive assignment for some of the other new hires on faculty. I think they wanted to take on the more challenging and difficult cases. What was interesting about my early experience was I working in outpatient surgery three or four times a week. As I worked with the same two hand surgeons, the same sports surgeon, and the same foot and ankle surgeon on a regular basis, we developed a really good relationship.

I always enjoyed regional anesthesia as a trainee. To be honest I didn’t think that regional anesthesia was a career choice, but when I started taking care of a lot of these patients at the outpatient surgery center I discovered how it could play a vital role. The surgeons and I would have discussions centered around the plan for surgery, the expected timeframe for pain, how often the patients would have to stay overnight for pain management, or how often patients historically would come back to the ER. We began planning our days the day before and go over the list together. I would propose plans in terms of regional anesthesia for each of the cases when it was indicated. I would also propose not using it when I didn’t think it was indicated.

Then I would call all the patients the day before and explain the anesthetic plan for their surgery. When I would see them the next day, I would introduce myself “I am Dr. Mariano, I spoke to you last night. Do you have any questions about what we’re going to do for you today?” There was no negative impact on efficiency despite integrating regional anesthesia into routine patient care. One of the interesting studies we did together actually showed that efficiency improved with the use of regional anesthesia, at least within the context of that model.

This change in how we approached each case had many positive outcomes. It improved patient care. It filled the need of the surgeons who wanted an efficient OR and to provide a good experience for their patients. And for me, it made me appreciate the importance of the relationship between anesthesiologists and surgeons. That’s really core to our specialty and even today, as anesthesiology grows into perioperative medicine, we should never give up taking care of patients in the operating room because that’s where the trusting relationship begins.

The other example I want to share is when I was working in outpatient surgery, a new chair of surgery started at UCSD. As part of his recruitment package he was promised a two-day breakout session to revamp the perioperative process. A consulting practice separated us into different groups and we broke up all the different steps from the decision to have surgery through convalescence. Following the event, the chair called and asked me if I would lead one of the work groups to revamp the preoperative evaluation clinic.

So I originally was hired to do peds. At this point I was doing mostly regional anesthesia and outpatient surgery in adults. I had even been asked by the residency director if I would teach the residents regional anesthesia, because they didn’t have a rotation set up yet. Now I was being asked if I would be willing to redesign the pre-op clinic.

So clearly this was not something that I thought was going to be in my future. But for some reason I thought it would be a good experience for me because I had never been part of a process improvement project. I told him up front that I didn’t see myself at the end of this as being the director of the clinic, but I’d be willing to head up the work group. What made this really interesting was each group had a champion that was one of the C-suite executives and mine was the hospital CEO.

Less than a year on faculty, I was having these very regular monthly or sometimes semi-monthly interactions with the CEO of the hospital. He was unique in many ways, and he was extremely down to earth. I would see him walking around on the two different campuses of UCSD serving up food in the cafeteria or sometimes walking on the wards. That was really eye-opening for me, especially as a new faculty member having gone through all of my residency and fellowship training with never having interacted with a C-suite executive.

To be able to have that interaction was invaluable. It created a level of confidence and comfort to approach administration and share innovations within healthcare and the operating room environment that were anesthesia-driven. “Here are some things that are new and we’re the only ones that are doing this in San Diego County.” Those kinds of initiatives were really of interest to our administration.

I always assumed that someone was letting them know what we were doing. However, what that whole experience taught me was that they don’t always know what’s going on and they should want to know. So, when you find receptive executives like that keep them informed and they can provide great support.

That really made a big difference for me early in my career in ways that I’ll never even know. It helped me in terms of establishing my own system of practice for anesthesiology, regional anesthesia and acute pain medicine.

BagMask: There are two things from that I think are very important to mention. One is just the power of yes and being open to new ideas. You never know where it’s going to lead. It could be the opportunity to meet new people or be invited to work on new projects. Second, you shared how you assumed the work you were doing was being passed along to the C-Suite. But that great work is not always being passed along. I think this revelation ties in great with a presentation you recently gave.

You talked about “The Biggest Threats to Anesthesia” and you listed three items: Loss of Identity. Fear of Technology. Resistance to change.

The thing that really stood out in my mind was the solution to Loss of Identity. It was “Establish a Brand”. I thought that was very powerful. Can you tell us about loss of identity and establishing brand and why it’s important to us?

Dr. Mariano: I think that this applies to healthcare professionals in general, but I do think specifically in terms of anesthesia professionals that there is a growing threat in becoming more and more anonymous. If you look at the trends in healthcare like these mega-mergers, you have pharmacy companies and insurance companies that are merging. You have private investment companies and traditional healthcare providers merging to form fairly innovative corporations centered around health and healthcare.

I think within the anesthesia community what we’re seeing is the growth of very large organizations that have the potential advantage of having strong contracting positions with hospitals which provides a level of job security for many individuals who practice anesthesia. But at the same time, I think that as we start to see more and more productivity-based incentives, and the corporatization of medicine and anesthesia practice, it doesn’t take a lot to think that much of what we do may become very much like making widgets.

You can imagine what a factory floor looks like and you know how each product is expected to look the same and how the individuals contribute to the various parts that go into forming that widget. They are basically nameless faceless producers that have very little identity.

That obviously is a dramatic extreme to some extent. But I do think that it’s a threat to me for a few reasons. I think that from a larger specialty perspective there’s the potential to discount the value that anesthesia services, perioperative medicine, and pain services can bring to the overall patient experience as well as the heavy influence that we can have on patient outcomes.

For the individual I worry because once a calling becomes a job, then I think that really leads down the road to what oftentimes is mistakenly called burnout. But I would probably categorize that into a loss of identity versus burnout, because I do think that they’re different. And what I mean by that is burnout, at least in the sense of overworking, is a problem that can be helped by self-care and by taking a well-timed vacation. Because to me burnout, or the product of overwork, still means intrinsically that you enjoy your work and that you still feel the calling.

The loss of identity is a bigger problem because for the healthcare professionals there’s a loss of a love for the profession and that’s really hard to recover from. There’s not enough time off or yoga that you can do to make you fall in love with your profession again.

So I think that the less value attributed to your work, to your contributions and to patient health and well-being are contributing factors that eat away at identity. I don’t think that all is lost. We must recognize the problems and then look for opportunities to reverse or prevent the loss of identity.

BagMask: One of the things I love that you said is it’s a problem when our calling becomes a job. There are two articles that you wrote four years apart that I believe really talked to your “Calling”. The first one you wrote was “What I Love about Being an Anesthesiologist” written in 2014. And then you followed it up in 2018 with, “Why I still love being an Anesthesiologist”. A couple of things, why did you think it was important to write this out, and how has it changed over the years for you?

Dr. Mariano: I appreciate your bringing those up. “What I Love about Being an Anesthesiologist” I wrote after ASA. Growing up, I didn’t necessarily know that I was going to be a physician. I remember taking my first job as a dishwasher because when you’re 16 and you just get your driver’s license, you have no experience and there aren’t that many other jobs that you’re qualified for.

The dishwashing job was at a senior assisted living facility and, after about a year of just washing dishes in the kitchen, I also started serving the residents either in the dining hall or delivering food to their apartments within the facility. I remember thinking that at some point when I finally figured out what I was going to do with my life, the concept of service would have to be part of my career. This is where I feel a job in health professions differs from a lot of other jobs.

I’m not saying that “job” itself is a negative term but it’s different. I think the difference between a job and a vocation, or a calling is there is always give and take. At the same time that you receive satisfaction, income and whatever it happens to be from the work that you produce, you also give something of yourself. And I think that’s the difference. When you’re in the health profession you intrinsically give something of yourself and that is part of the reward or at least that’s the investment that you put in that helps deliver a reward.

The role of the anesthesiologist is very unique within medicine. There are a lot of aspects to anesthesiology that many people don’t consider necessarily the role of a physician, but that’s actually what makes it so appealing to me. As an anesthesiologist I provide the most personalized form of medicine or, to phrase it another way, the most direct patient care.

When I’m taking care of a patient who is under general anesthesia, that person can’t speak for him or herself or can’t act for him or herself. That kind of responsibility is very different than every other physician role that I can think of in the hospital. The fact that we have to administer our own medications. We have to establish intravenous access for our patients in order to even treat them in the first place and to provide anesthesia. The fact that all the procedures that are required for our patient are done by us and then are used by us in the practice of anesthesia care.

I think it is important that as an anesthesiologist you must, by nature, learn how to work within a team because we are team. One of the powerful moments for me in every surgery is when we do a pre-surgical time out. It’s when you go through the checklist and then everyone introduces themselves to each other and everyone knows that you are all here for this one person.

I sometimes think that moment is understated. As anesthesiologists, our medical specialty exists only to make sure patients are safe and that they have a positive experience and outcome after having surgery and invasive procedures. That has to be something that each anesthesiologist has to consider and take with him or herself every time they bring a patient into the operating room.

I think because it’s a very cerebral profession in many ways, it’s hard for someone on the outside to see what an anesthesiologist is doing. So much of what we do is internal processing of information and anticipating outcomes. As anesthesia professionals, we should try to explain and share with people our thought process and our plan to achieve a safe outcome.

The time that we have to establish trust with patients and their caregivers before we bring patients to the operating room is very brief. The more patients understand what we think about and how important we take our responsibility gives them the confidence they are in good hands and promotes us as a profession. That’s why I wrote that initial article and then the follow-up one came about after attending a party with my wife.

It was the usual cocktail party conversation and the question came up of what do you do and what’s that like. It got me thinking about not only how much I still enjoy and love being an anesthesiologist, but how much more I enjoy it now.

My career has taken a lot of different directions, but I’ve always tried to follow a “One Degree of Separation Rule”. When I’m at the bedside taking care of a patient or I’m in the operating room, that is zero degrees of separation. Everything that I do will be for the patient and to improve that patient’s outcome and experience.

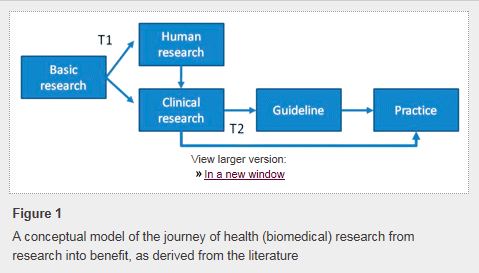

But when I’m doing research, teaching in the classroom, presenting at a conference, or sitting in an administrative meeting, that is “One Degree of Separation” from a patient. When I answer a research question, I can share that knowledge and someone else can then use that information to help his or her patients. When I’m teaching our fellows or residents or presenting at a national conference, they will go out and hopefully use that information to take better care of their patients.

And when I sit in an administrative meeting, it’s not unusual for me to be the only person there that has actually laid a hand on a patient within the last several years. Those are times when I feel like I’m representing not just the clinicians but I’m representing our own patients. What I say and contribute in those meetings helps create informed policies that will make it easier for our colleagues to take better care of their patients.

It is those aspects of my job that have kept me not just excited about it, but still in love with it and excited about looking forward to the future.

BagMask: I have one last question for you. What is your hope for all the anesthesia providers during this time with so many changes in health care?

Dr. Mariano: My hope for all anesthesia professionals is that they take to heart the importance of what they do. They have to recognize their importance, because as anesthesia practices continue to grow and performance metrics continue to develop, there’s an over emphasis on productivity. As these trends continue, I really want anesthesia professionals to continue to understand their own value.

I want them to look for the opportunities to take one more step. As an example, you are taking great care of your patients and you’ve assessed a patient who has a history of postoperative nausea attributed to every type of opioid they have taken in the past. You develop and carry out an opioid-free anesthesia plan or you provide the appropriate interventions to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting and that patient ends up doing really well.

Take the next step. The next step is let your surgeon know. Let your bosses know. Let your director of perioperative services know. What you’ve provided is exactly what everyone is trying to achieve when they talk about personalized medical care. And you’ve done that. Sometimes we don’t recognize it, but this is a huge opportunity. We do have a tendency to be anonymous, but we should highlight positives that are associated with our practice. The more attention that is brought to the good work that we’re doing not only helps promote our specialty, but more importantly helps us as individuals in terms of enjoying our career, feeling satisfied and always finding a reason to love practicing anesthesia.

If you still need more convincing, this

If you still need more convincing, this

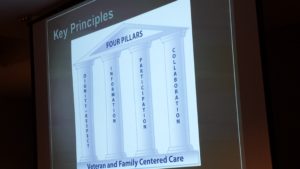

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at