We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated, “acute” pain (new onset, often with an identifiable cause) must be aggressively managed and, ideally, eliminated. This requires a systems-based approach led by physicians dedicated to understanding acute pain pathophysiology and investigating new ways to treat it.

We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated, “acute” pain (new onset, often with an identifiable cause) must be aggressively managed and, ideally, eliminated. This requires a systems-based approach led by physicians dedicated to understanding acute pain pathophysiology and investigating new ways to treat it.

In December 2013, I submitted a 161-page letter to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requesting that regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine be considered for fellowship accreditation, with a lot of help from a small group of fellowship directors and colleagues from obstetric anesthesiology who recently went through the ACGME accreditation process for their fellowships. With no requests for further information, the Board of Directors of the ACGME informed me in the fall of 2014 that Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine (RAAPM) will be the next accredited subspecialty fellowship within the core discipline of Anesthesiology. The draft program requirements have been posted online for public comments. After the comment period, these program requirements will be revised and then finalized for posting by the ACGME. At that point, which may be as early as the end of this year, institutions with RAAPM fellowships will be invited to apply for accreditation.

I have received many questions from ASRA members about this process to date, so below I have provided some of my answers to the most common ones:

Why do we need “another” fellowship dedicated to pain medicine? Although we already have a board-certified subspecialty of Pain Medicine within Anesthesiology, there is a growing demand for physicians who specialize in hospital-based acute pain medicine. For Pain Medicine fellows, the required “Acute Pain Inpatient Experience” may be satisfied by documented involvement with a minimum of only 50 new patients and the spectrum of pain diagnoses and treatments that they are required to learn during one year is vast. Further, Pain Medicine is a board-certified subspecialty of Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Psychiatry and Neurology, in addition to Anesthesiology; graduates from any of these residency programs can be accepted into the one-year Pain Medicine fellowship and will not be as familiar with surgical or trauma-induced acute pain as an anesthesiology residency graduate. Anesthesiology is a hospital-based medical specialty, and anesthesiologists are physicians who focus on a daily basis on the prevention and treatment of pain for their patients who undergo surgery, suffer trauma, or present for childbirth. History also supports the evolution of acute pain medicine through anesthesiology. The concept of an anesthesiology-led acute pain management service was described first in 1988 (1), but arguably the techniques employed in modern acute pain medicine and regional anesthesiology date back to Gaston Labat’s publication of Regional Anesthesia: Its Technic and Clinical Application in 1922, with advancement and refinement of this subspecialty in the 1960s and 1970s (2-6). Finally, a recent survey study shows that the great majority (83.7%) of practicing pain physicians in the United States focus only on chronic pain (7).

Why do anesthesiology residency graduates still need to do a fellowship in RAAPM? By the time they complete the core residency in anesthesiology today, not all residents have gained sufficient clinical experience to provide optimal care for the complete spectrum of issues experienced by patients suffering from acutely painful conditions, including the ability to reliably provide advanced interventional techniques proven to be effective in managing pain in the acute setting (8-12). We need physician leaders who can run acute pain medicine teams and design systems to provide individualized, comprehensive, and timely pain management for both medical and surgical patients in the hospital, expeditiously managing requests for assistance when pain intensity levels exceed those set forth in quality standards, or to prevent pain intensity from reaching such levels. The mission statement for the Acute Pain Medicine Special Interest Group within the American Academy of Pain Medicine provides clear justification.

Will RAAPM fellowship graduates get jobs when they are done? Although no one can make this guarantee, there are good reasons to think that there will be growing demand for RAAPM graduates in the future. In a survey of fellowship graduates and academic chairs published in 2005, 61 of 132 of academic chairs responded (46%), noting that future staffing models for their department will likely include an average of two additional faculty trained in regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine (13). RAAPM fellowship graduates are the only physicians who can say that their subspecialty training is entirely dedicated to improving the patient experience. The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey is administered to a random sample of patients who have received inpatient care and receive government insurance through Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The survey consists of 32 questions and is intended to assess the “patient experience of care” domain in the value-based purchasing program. A hospital’s survey scores are publicly disclosed and make up 30% of the formula used to determine how much of its diagnosis-related group payment withholding will be paid by CMS at the end of each year. Of the 32 questions, 7 directly or indirectly relate to in-hospital pain management.

Are we ready for accreditation? Currently, there are over 60 institutions in the United States and Canada that list themselves as having nonaccredited fellowship training programs focused on RAAPM on the ASRA website. Since 2002, the group of regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine fellowship directors has been meeting twice yearly at the ASRA Annual Spring Meeting and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Annual Meeting in the fall. Despite not being an ACGME-accredited fellowship, this group, has been voluntarily engaged in developing and refining training guidelines as the foundation for the fellowship. These guidelines, originally published in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine in 2005 (14) with a revision in 2011 (15) have been recently released as the third edition (16). Formal ACGME program requirements will serve as a measuring stick to hopefully ensure that the certificates that RAAPM fellowship graduates receive from all accredited programs will share some common value.

As with other medical subspecialties, acute pain medicine has emerged due to the need for trained specialists—in this case, those who possess the knowledge, skills, and abilities to efficiently manage a high volume of inpatient consultations, anticipate the analgesic needs of a wide range of patients based on preoperative risk, use a multimodal approach to manage and prevent pain when possible, and aggressively treat severe acute pain when it occurs to prevent it from transitioning into chronic pain. The RAAPM fellowship graduate must be a physician leader who is capable of collaborating with other healthcare providers in anesthesiology, surgery, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy, and more to establish multidisciplinary programs that add value and improve patient care in the hospital setting and beyond.

This article originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of ASRA News. As of October 2016, the regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine is the newest accredited subspecialty fellowship within anesthesiology, and programs may now apply for accreditation to the ACGME.

REFERENCES

- Ready LB, Oden R, Chadwick HS, Benedetti C, Rooke GA, Caplan R, Wild LM. Development of an anesthesiology-based postoperative pain management service. Anesthesiology. 1988; 68:100-6.

- Winnie AP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z. The inguinal paravascular technic of lumbar plexus anesthesia: the “3-in-1 block.” Anesth Analg. 1973; 52:989-96.

- Winnie AP, Collins VJ. The subclavian perivascular technique of brachial plexus anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1964; 25:353-63.

- Raj PP, Montgomery SJ, Nettles D, Jenkins MT Infraclavicular brachial plexus block–a new approach. Anesth Analg. 1973; 52:897-904.

- Raj PP, Parks RI, Watson TD, Jenkins MT. A new single-position supine approach to sciatic-femoral nerve block. Anesth Analg. 1975; 54:489-93.

- Raj PP, Rosenblatt R, Miller J, Katz RL, Carden E. Dynamics of local-anesthetic compounds in regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1977; 56: 110-7.

- Breuer B, Pappagallo M, Tai JY, Portenoy RK. U.S. board-certified pain physician practices: uniformity and census data of their locations. J Pain. 2007; 8: 244-50.

- Buvanendran A, Kroin JS. Multimodal analgesia for controlling acute postoperative pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009; 22: 588-93.

- Hebl JR, Dilger JA, Byer DE, Kopp SL, Stevens SR, Pagnano MW, Hanssen AD, Horlocker TT. A pre-emptive multimodal pathway featuring peripheral nerve block improves perioperative outcomes after major orthopedic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008; 33: 510-7.

- Jin F, Chung F. Multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain control. J Clin Anesth. 2001; 13: 524-39.

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg. 1993; 77: 1048-56.

- Young A, Buvanendran A.Recent advances in multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012; 30: 91-100.

- Neal JM, Kopacz DJ, Liguori GA, Beckman JD, Hargett MJ. The training and careers of regional anesthesia fellows–1983-2002. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005; 30: 226-32.

- Hargett MJ, Beckman JD, Liguori GA, Neal JM. Guidelines for regional anesthesia fellowship training. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005; 30: 218-25.

- Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine Fellowship Directors Group. Guidelines for fellowship training in regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine: second edition, 2010. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2011; 36: 282-8.

- Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine Fellowship Directors Group. Guidelines for fellowship training in regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine: third edition, 2014. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015; 40: 213-7.

Facebook

LinkedIn

Pinterest

E-mail

Related Posts:

San Francisco is the biggest little city. At just under 47 square miles and with more than 800,000 inhabitants, San Francisco is second only to New York City in terms of population density. Despite its relatively small size, “the City” (as we suburbanites refer to it) consists of many small neighborhoods, each with its own charm and character: Union Square, the Financial District, Pacific Heights, the Marina, Haight-Ashbury, Chinatown, Little Italy, Nob Hill, Russian Hill, SoMa (South of Market), the Fillmore, Japantown, Mission District, Noe Valley, Twin Peaks, Castro, Sunset, Tenderloin, and others. This is probably why die-hard New Yorkers love it so much.

San Francisco is the biggest little city. At just under 47 square miles and with more than 800,000 inhabitants, San Francisco is second only to New York City in terms of population density. Despite its relatively small size, “the City” (as we suburbanites refer to it) consists of many small neighborhoods, each with its own charm and character: Union Square, the Financial District, Pacific Heights, the Marina, Haight-Ashbury, Chinatown, Little Italy, Nob Hill, Russian Hill, SoMa (South of Market), the Fillmore, Japantown, Mission District, Noe Valley, Twin Peaks, Castro, Sunset, Tenderloin, and others. This is probably why die-hard New Yorkers love it so much. San Francisco is very family-friendly. If you’re debating whether or not to make a family trip out of #ANES18, my advice is to do it. Right around the convention center there are a number of attractions and events worth checking out. I highly recommend visiting the farmers market at the Ferry Building. While there, you can also take a ferry ride to a number of other destinations in the Bay Area (try Sausalito, a short trip that takes you past Alcatraz). For kids, there are parks within walking distance as well as the Children’s Creativity Museum, the San Francisco Railway Museum, Exploratorium, and the cable car turnabout at Powell and Market Street. Trips to Fisherman’s Wharf, Ghiradelli Square, or the aquarium are a short taxi or cable car ride away. In addition, runners will love running up and down the Embarcadero which gives you a view of the Bay Bridge and takes you past the City’s many piers. Shoppers will be in heaven, and foodies will have to make the impossible decision of choosing where to eat for every meal.

San Francisco is very family-friendly. If you’re debating whether or not to make a family trip out of #ANES18, my advice is to do it. Right around the convention center there are a number of attractions and events worth checking out. I highly recommend visiting the farmers market at the Ferry Building. While there, you can also take a ferry ride to a number of other destinations in the Bay Area (try Sausalito, a short trip that takes you past Alcatraz). For kids, there are parks within walking distance as well as the Children’s Creativity Museum, the San Francisco Railway Museum, Exploratorium, and the cable car turnabout at Powell and Market Street. Trips to Fisherman’s Wharf, Ghiradelli Square, or the aquarium are a short taxi or cable car ride away. In addition, runners will love running up and down the Embarcadero which gives you a view of the Bay Bridge and takes you past the City’s many piers. Shoppers will be in heaven, and foodies will have to make the impossible decision of choosing where to eat for every meal.

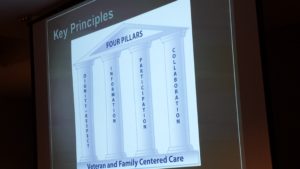

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Live tweeting during a scientific conference offers many benefits. For attendees at the meeting, it allows sharing of learning points from multiple concurrent sessions. This also decreases the incidence of “FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)” since you can only be in one session at any given time but can learn vicariously through others. For your Twitter community outside the meeting venue, your live tweeting can help to disseminate the key messages from the conference to a broader audience and ultimately may facilitate changes in clinical practice.

Live tweeting during a scientific conference offers many benefits. For attendees at the meeting, it allows sharing of learning points from multiple concurrent sessions. This also decreases the incidence of “FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)” since you can only be in one session at any given time but can learn vicariously through others. For your Twitter community outside the meeting venue, your live tweeting can help to disseminate the key messages from the conference to a broader audience and ultimately may facilitate changes in clinical practice.

We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated,

We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated,