Not all pain is the same.

Chronic pain can be palliated, but “acute” pain (new onset, often with an identifiable cause) must be stamped out. This requires a systems-based approach led by physicians dedicated to understanding acute pain pathophysiology and investigating new ways to treat it. The solution is definitely not giving more and more opioids.

Chronic pain can be palliated, but “acute” pain (new onset, often with an identifiable cause) must be stamped out. This requires a systems-based approach led by physicians dedicated to understanding acute pain pathophysiology and investigating new ways to treat it. The solution is definitely not giving more and more opioids.

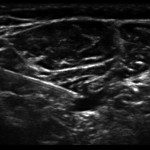

As our understanding of pain mechanisms has evolved, select physicians have developed a special focus on pain in the acute injury/illness and perioperative settings that has led to the rapid advancement of systemic and site-specific interventions to effectively manage this type of pain. Acute pain medicine involves the routine use of multiple modalities concurrently (i.e., multimodal analgesia) in the in-hospital setting to reduce the intensity of acute pain and minimize the development of debilitating persistent pain, a problem that can result from even common surgical procedures or trauma. Unfortunately, the need for specialists in acute pain medicine is increasing.

In December of 2013, I submitted a 161 page letter to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requesting that regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine be considered for fellowship accreditation with the help of my fellowship director colleagues. The Board of Directors of the ACGME informed me this past fall (2014) that they have approved our fellowship to be the next accredited subspecialty within anesthesiology.

Wait – don’t we already have a fellowship program in pain medicine? Yes we do, and this one year post-residency program does include the “Acute Pain Inpatient Experience.” However, this requirement may be satisfied by documented involvement with a minimum of only 50 new patients and is not the primary emphasis of fellowship training in the specialty. Pain medicine is a board-certified subspecialty of anesthesiology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and psychiatry and neurology; graduates from any of these residency programs can apply to the one year program. In a recent survey study of practicing pain physicians in the United States with added qualification in pain management according to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the great majority (83.7%) of respondents defined their practices as following “chronic pain patients longitudinally” (1).

There is clearly room and a need for a subspecialty training program in acute pain medicine that can focus on improving the in-hospital pain experience. Such a program should advance, in a positive and value-added fashion, the present continuum of training in pain medicine.

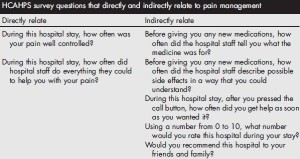

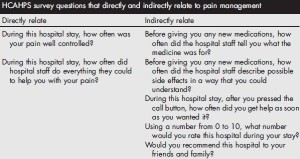

The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey is administered to a random sample of patients who have received inpatient care and receive government insurance through Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The survey consists of 32 questions and is intended to assess the “patient experience of care” domain in the value-based purchasing program. A hospital’s survey scores are publicly disclosed and make up 30% of the formula used to determine how much of its diagnosis-related group payment withholding will be paid by CMS at the end of each year. Of the 32 questions, 7 directly or indirectly relate to in-hospital pain management.

The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey is administered to a random sample of patients who have received inpatient care and receive government insurance through Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The survey consists of 32 questions and is intended to assess the “patient experience of care” domain in the value-based purchasing program. A hospital’s survey scores are publicly disclosed and make up 30% of the formula used to determine how much of its diagnosis-related group payment withholding will be paid by CMS at the end of each year. Of the 32 questions, 7 directly or indirectly relate to in-hospital pain management.

Why should acute pain medicine be a subspecialty of anesthesiology? Anesthesiology is a hospital-based medical specialty, and anesthesiologists are physicians who focus on the prevention and treatment of pain for their patients who undergo surgery, suffer trauma, or present for childbirth on a daily basis. For more details on the role of the anesthesiologist, please see “Physicians specializing in the patient experience.” Further, history supports the evolution of acute pain medicine through anesthesiology. The concept of an anesthesiology-led acute pain management service was described first in 1988 (2), but arguably the techniques employed in modern acute pain medicine and regional anesthesiology date back to Gaston Labat’s publication of Regional Anesthesia: its Technic and Clinical Application in 1922, with advancement and refinement of this subspecialty in the 1960s and 1970s (3-7).

By the time they complete the core residency in anesthesiology today, not all trainees have gained sufficient clinical experience to provide optimal care for the complete spectrum of issues experienced by patients suffering from acutely painful conditions, including the ability to reliably provide advanced interventional techniques proven to be effective in managing pain in the acute setting (8-12). We need physician leaders who can run acute pain medicine teams and design systems to provide individualized, comprehensive, and timely pain management for both medical and surgical patients in the hospital, expeditiously managing requests for assistance when pain intensity levels exceed those set forth in quality standards, or to prevent pain intensity from reaching such levels. The mission statement for the Acute Pain Medicine Special Interest Group within the American Academy of Pain Medicine provides additional justification.

In a survey of fellowship graduates and academic chairs published in 2005, 61 of 132 of academic chairs responded (46%), noting that future staffing models for their department will likely include an average of 2 additional faculty trained in regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine (13).

Currently, there are over 60 institutions in the United States and Canada that list themselves as having non-accredited fellowship training programs focused on regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine on the ASRA website. Since 2002, the group of regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine fellowship directors has been meeting twice yearly at the ASRA Spring Annual Meeting and ASA Annual Meeting which takes place in the fall. Despite not being an ACGME-accredited fellowship, this group, recognizing the lack of formalized training guidelines, voluntarily began to develop such guidelines as the foundation for subspecialty fellowship training in existing and future programs. These guidelines were originally published in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine in 2005 (14), then were subsequently reviewed, revised, and published as the 2nd edition in 2011 (15), and have been recently updated again (16).

As with other subspecialties, acute pain medicine has emerged due to the need for trained specialists—in this case, those who understand the complicated, multi-faceted disease processes of acute pain, and its potential continuity with chronic pain, and can apply appropriate medical and interventional treatment in a timely fashion. The fellowship-trained regional anesthesiologist and acute pain medicine specialist must be capable of collaborating with other healthcare providers in anesthesiology, surgery, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy, and more to establish multidisciplinary programs that add value and improve patient care in the hospital setting and beyond.

REFERENCES

- Breuer B, Pappagallo M, Tai JY, Portenoy RK: U.S. board-certified pain physician practices: uniformity and census data of their locations. J Pain 2007; 8: 244-50

- Ready LB, Oden R, Chadwick HS, Benedetti C, Rooke GA, Caplan R, Wild LM: Development of an anesthesiology-based postoperative pain management service. Anesthesiology 1988; 68: 100-6

- Winnie AP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z: The inguinal paravascular technic of lumbar plexus anesthesia: the “3-in-1 block”. Anesth Analg 1973; 52: 989-96

- Winnie AP, Collins VJ: The Subclavian Perivascular Technique of Brachial Plexus Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1964; 25: 353-63

- Raj PP, Montgomery SJ, Nettles D, Jenkins MT: Infraclavicular brachial plexus block–a new approach. Anesth Analg 1973; 52: 897-904

- Raj PP, Parks RI, Watson TD, Jenkins MT: A new single-position supine approach to sciatic-femoral nerve block. Anesth Analg 1975; 54: 489-93

- Raj PP, Rosenblatt R, Miller J, Katz RL, Carden E: Dynamics of local-anesthetic compounds in regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1977; 56: 110-7

- Buvanendran A, Kroin JS: Multimodal analgesia for controlling acute postoperative pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22: 588-93

- Hebl JR, Dilger JA, Byer DE, Kopp SL, Stevens SR, Pagnano MW, Hanssen AD, Horlocker TT: A pre-emptive multimodal pathway featuring peripheral nerve block improves perioperative outcomes after major orthopedic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2008; 33: 510-7

- Jin F, Chung F: Multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain control. J Clin Anesth 2001; 13: 524-39

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB: The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg 1993; 77: 1048-56

- Young A, Buvanendran A: Recent advances in multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2012; 30: 91-100

- Neal JM, Kopacz DJ, Liguori GA, Beckman JD, Hargett MJ: The training and careers of regional anesthesia fellows–1983-2002. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005; 30: 226-32

- Hargett MJ, Beckman JD, Liguori GA, Neal JM: Guidelines for regional anesthesia fellowship training. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005; 30: 218-25

- Guidelines for fellowship training in Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine: Second Edition, 2010. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011; 36: 282-8

- Guidelines for fellowship training in Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine: Third Edition, 2014. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40: 213-7

Facebook

LinkedIn

Pinterest

E-mail

Related Posts:

I am a physician, clinical researcher, and educator.

I am a physician, clinical researcher, and educator.

re administering a medication, it’s not enough just to understand the complex pharmacologic effects of the drug and determine the right dose. The anesthesiologist also has to know how to dilute and prepare the drug, the appropriate route for the medication, which other medications are and are not compatible, and how to program the infusion device. In addition, an anesthesiologist has to be technically skilled at finding veins—sometimes in the hand or arm, sometimes leading centrally to the heart—in order to give the medication in the first place.

re administering a medication, it’s not enough just to understand the complex pharmacologic effects of the drug and determine the right dose. The anesthesiologist also has to know how to dilute and prepare the drug, the appropriate route for the medication, which other medications are and are not compatible, and how to program the infusion device. In addition, an anesthesiologist has to be technically skilled at finding veins—sometimes in the hand or arm, sometimes leading centrally to the heart—in order to give the medication in the first place.