This post was first released on KevinMD.com.

Putting physicians in charge of hospitals seems like a no-brainer, but it isn’t what usually happens unfortunately. A study published in Academic Medicine states that only about 4% of hospitals in the United States are run by physician leaders, which represents a steep decline from 35% in 1935. In the most recent 2018 Becker’s Hospital Review “100 Great Leaders in Healthcare,” only 29 are physicians.

The stats don’t lie, however. Healthcare systems run by physicians do better. When comparing quality metrics, physician-run hospitals outperform non-physician-run hospitals by 25%. In the 2017-18 U.S. News & World Report Best Hospitals Honor Roll, the top 4 hospitals (Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital) have physician leaders. Similar findings have been reported in other countries as well.

While not all physicians make good leaders, those that do really stand out. For those physicians who may consider applying for hospital leadership positions, there are certain characteristics that should distinguish them from non-physician applicants and help them make the transition successfully. Of course, this is my opinion, but I think it comes down to these 5 things:

- Physicians are bound by an oath. The Hippocratic Oath in some form is recited by every medical school graduate around the world. This oath emphasizes that medicine is a calling and not just a job: “May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.” Physicians commit themselves to the treatment of disease and the health of human beings. There is no similar oath for non-physician healthcare executives.

- Physicians know how to make tough decisions. This is crucial to every informed consent process. Physicians need to curate available evidence, weigh risks and benefits, and share their recommendations with patients and families in situations that can literally be life or death. This is essential to the art of medicine. Effectively translating technical jargon into language that lay people can understand allows others to participate in the decision making process. This applies both to the bedside and the boardroom.

- Physicians are trained improvement experts. They learn the diagnostic and treatment cycle which requires listening to patients (also known as taking a history), evaluating test results, considering all possible relevant diagnoses, and instituting an initial treatment plan. As new results emerge and the clinical course evolves, the diagnosis and treatment plan are refined. In my medical specialty of anesthesiology, this cycle occurs rapidly and often many times during a complex operation. These skills translate well to diagnosing and treating sick healthcare systems.

- Physicians are lifelong learners. When laparoscopic surgical techniques emerged, surgeons already in practice had to find ways to learn them or be left behind. Medicine is always changing. To maintain medical licensure, physicians must commit many hours of continuing medical education every year. New research articles in every field of medicine are published every day. For these reasons, physicians cannot hold onto “the way it has always been done,” and this attitude serves them well in healthcare leadership.

- Physicians work their way up. Every physician leader started as an intern, the lowest rung of the medical training ladder. Interns rotate on different services within their specialty, working in a team with higher-ranked residents under the supervision of an attending physician. As physicians progress in training through their years of residency, they get to know more and more hospital staff in other disciplines and take on more patient care responsibility. A very important lesson learned during residency is that the best ideas can come from anyone; occasionally the intern comes up with the right diagnosis when more senior team members cannot.

While these qualities are necessary, they are not sufficient. To be effective healthcare leaders, physicians need to develop their administrative skills in personnel management, team building, and strategic planning. They will have to learn to understand and manage hospital finances, meet regulatory requirements and performance metrics, and find ways to support and drive innovation. For physicians who have already completed their medical training, a commitment to effective healthcare leadership will require as much time and dedication as their medical studies. However, if they don’t do this, there are plenty of non-physicians who will.

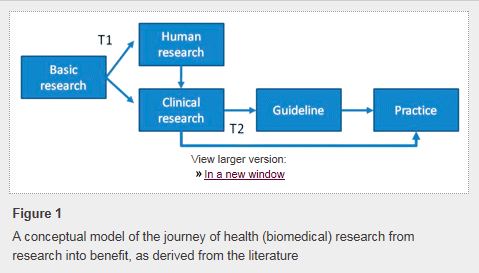

Changing physician behavior is rarely easy, and studies show that it can take

Changing physician behavior is rarely easy, and studies show that it can take